It’s been a very quiet (writing-wise) couple of months for me. I had this feeling of emptiness (mind-wise) with not many thoughts in my head. I was really questioning it—when you’re spending summer seeing the world, shouldn’t you have more to talk about? I also wondered if something had died in me; if I’d lost something, if I’d become more detached and unfeeling. Now when I’m thinking about it I think it’s maybe more of the opposite. For context I travelled quite a bit this past summer. Ironically, the more I travelled, the less sure I felt of myself and the world. When you are faced with the vastness of the world, you become aware of what you do not know; not about the world, nor about yourself. You stand before the knowledge that you are truly nothing in the face of everything. Who am I to write my opinion on anything? Despite everything wrong in the world sometimes it is just beautiful to be able to exist within the great big universe that I will never get to know completely.

A couple of months ago I was in conversation with a couple of friends—some of the brightest minds I’ve been around—about the concept of city-consciousness. Actually, one of them had written her entire literature thesis on this idea; where a book or story is not just about the plot itself or the individual character, but the city and environment in which they exist. I’ve always wondered about the Singaporean consciousness. I can’t think of any book I’ve read (not that I’ve read much Singaporean literature) that I felt authentically captured this. When I mentioned this to the same friends who made their appearance at the start of this piece, I mentioned how mournful I was at this empty gap, a chasm of literature where this collective consciousness should’ve manifested itself and it hasn’t. Singapore was so intense, so rich, I told them, it would be a very difficult book to write but one worth reading. One of my friends questioned why I didn’t choose to write it. “It’s too difficult”, I said. “I’m not Singaporean enough, I could never do justice to it.”

It was during the modernist era that this idea of consciousness came about, when theories of consciousness (or the unconscious) in psychology and psychoanalysis first emerged in Europe. So therefore (initially European) modernist texts were incubators for these ideas of consciousness, not just individual, but expanding towards something collective; the environment of the city. Himanshu Dutta writes how the city “is marked by an awareness of the spatiotemporal coordinates within which each work is located”. With the more specific being London in Woolf’s Mrs Dalloway, Dublin in Joyce’s Ulysses and Dubliners, Paris in Rhys’ Good Morning, Midnight; and the broader being not particular cities but depictions of the post-industrialist urban structures. The city acted less like a space or background, and more like a character, which moulded and interacted with the human condition — creating and being created by its inhabitants.(I’m doing a terrible job at explaining this; some modernist academic somewhere is violently throwing up.) When I was scouring the internet on this topic, I stumbled on this strange conversation between man and AI about urban consciousness (ironic). I think it is worth a read as a whole, making references to Lacan’s theories of unconsciousness and alterity; but what I wanted to quote from it is its definition of a city-consciousness: “Some people might say that a city’s consciousness is its collective identity, or the sum of all its residents’ individual consciousnesses. Others might say that a city has its own unique consciousness, separate from its residents.”

There are some cities with a very notable collective consciousness. American cities are probably the most famous, considering the amount of media that the country exudes. With New York — films like Taxi Driver, When Harry Met Sally (and literally every rom-com ever), Frances Ha, etc.; songs like Billy Joel’s Piano Man, Jay-Z’s Empire State of Mind, and honestly every other American song that I’m kind of lazy to list; books like Baldwin’s Another Country, Ellison’s Invisible Man, Auster’s City of Glass, Brand’s The Outward Room; shows like Sex and the City, FRIENDS. The consciousness of Los Angeles, to me, seems to adapt as definitions of fame and Hollywood also evolve and mutate. Cities like Hong Kong, Paris, Tokyo, Bombay, Calcutta, Seoul;—there are definite characters that are intensely and deeply-rooted in the experiences of the cities, and these present themselves before you in the media they inhabit as well.

Most places, I feel, have a very evident, throbbing character; I’m no longer talking about the portrayal or immortalisation of a city in media, but rather the physical experience of such. I felt this so intensely when I travelled back-to-back to so many places. When you’re thrust somewhere new you’re suddenly aware of everything that is alive even in the lifeless objects around you; suddenly the metro feels alive, and the roads talk to you. Weirdly you understand what the modernist writers were on about. When Mady came to Singapore I felt a sense of panic - what do I show her? I knew she’d stayed here for her teens and knew what Singapore was like but I suddenly felt an immense pressure to show her what it was really, truly about. When we walked around together I was so acutely aware of the city; every noise, every person, every sight. It felt like I was experiencing it anew, critiquing it through her lens. It made me question myself—like most Singaporeans I often complained about living in Singapore. This weird panic of needing Mady to see something profound in it confused me about my own affections towards the country. Why did I love it so much? Why did I want her to like it so badly? Did I really like living here, was this a home to me? Or was it just a massive comfort zone that I was stuck in? She’d been to every city ever, she lives in one of the most famous, most romanticised cities; what did Singapore compare to all that? What brilliant, overwhelming character did it inhabit?

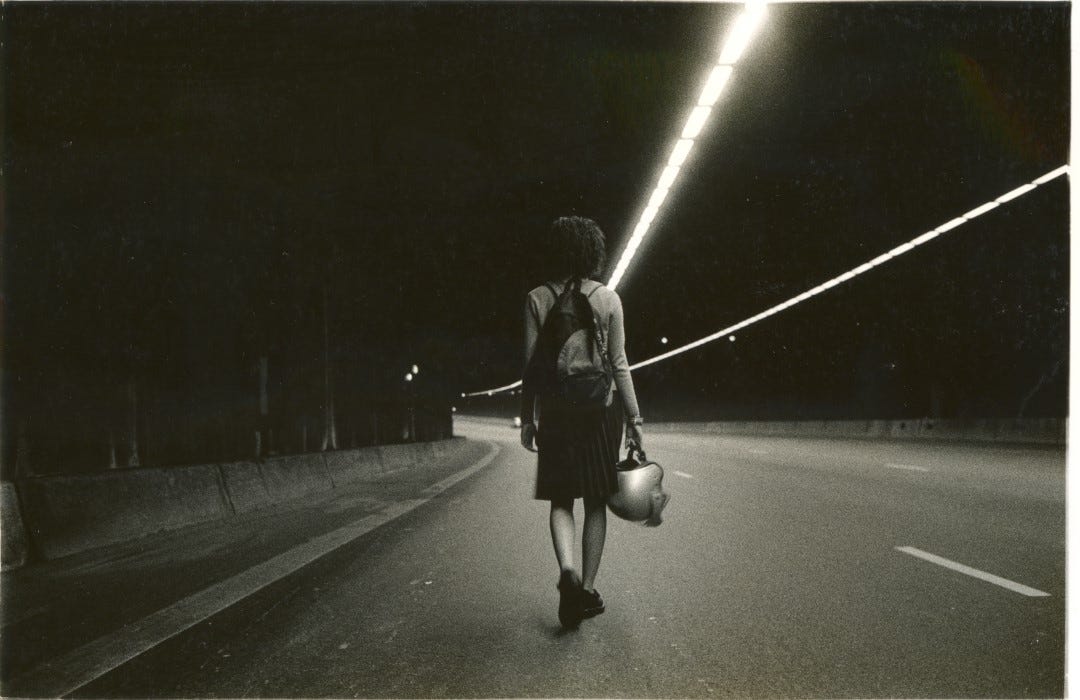

Perhaps it is me—the kid grown up on a precipice, that is not able to immediately grasp the Singaporean consciousness because I haven’t been privy to it. I always think of this as the go-to excuse; “I don’t know it well enough! I’m not local enough!” Or maybe I’ve gotten too accustomed to it, that I don’t take note of its quirks. This year I watched a lot more Singaporean films than I have ever done—4!—this made me wonder if film could capture that collective consciousness better. Of the four, three were dated: Bugis Street (1990), Eating Air (1999) and The Road Less Travelled (1997). Eating Air and The Road Less Travelled seemed to not just present the individual lives of the characters, but preserve the visceral consciousness embedded in the minds of the people at that time (#Y2K #TheNewMillenium). Maybe it was the vintage film aesthetic of those days that made it seem all the more romantic - the thrill of being young, wild and free in Singapore; the environment pregnant with possibilities that threatened to burst around you; the easy camaraderie; the culture. Yet it felt like looking at something that had been lost, a sort of history that had been sanitised and wiped over (by the state?) and forgotten. In that temporary limbo between reality and fiction I suddenly understood the psyche of the city that the film was presenting. It seemed Singapore had a consciousness after all; it’s just something very well-hidden behind the soulless façade, or maybe evolved past recognition. Now we have Crazy Rich Asians and other caricatures that define Singapore in cinema.

Maybe it’s also because film has the unfair advantage of capturing an experience so visceral that it feels real compared to other forms of media. Sometimes you get to watch a film so beautiful and passionate that for the moment you are one of the characters, sharing the experience. Now that I’m looking back at it all, I think it’s unfair of me to only have gained awareness of the Singapore-consciousness by watching a film. But I’d argue and say that would be the reason for all of us making a sort of statement on whether a city has character or not—when we watch a film that is successful in convincing us of it, perhaps. We all agree the same cities have a certain character—often without even stepping foot there—because it’s been shown to us, and we’ve gotten used to it. Why do we all get nostalgic listening to John Denver’s Take Me Home, Country Roads? Most of us aren’t even from West Virginia, Alabama. Does the city-consciousness shape us? Or have we become attached to psyches of cities shaped by others? I don’t know. This could be an endless loop of cyclical dependency.

In the Aesop fable The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse, the story revolves around the town mouse and the country mouse (obviously). The town mouse visits his cousin the country mouse who prepares “simple country cuisine”, which the town mouse scoffs at. He invites his cousin over to his, to show him the “real deal”, but while they’re feasting on the finest fare a cat comes to try and eat them, and they run in fear of their lives. And then the country mouse is content with his simple life. I don’t really know why this fable came to mind writing this (I haven’t thought of this in ages). Neither is it really related to anything I’ve written about. Actually I’m not particularly sure what this piece of writing is about. A renewed appreciation of the world? A renewed appreciation of the city I take for granted? A renewed appreciation of myself? I’m taking it as an exercise in writing. (Arguably the real exercise in writing would be to actually distill the Singaporean consciousness in words, but I think that’s for another day or another person.) (Also, Aesop lived in the ages where towns were the biggest deal. I wonder what he would think of cities.) I guess the moral of the story is to be content with what you have. Or indulge in a more active relationship with the environment you’re in.

This video ↑ was taken in Chinatown during Lunar New Year season this year.

Wonder how you feel about all of this in a year's time