Pseudo-independence

Thoughts about living alone while on exchange

Almost exactly a month ago I went to my first concert alone. This was completely unplanned and out of character for me. The whole week before the concert I was trying not to meltdown too obviously, begging people to buy the spare ticket, texting my sister nonstop about how nauseous I was at the prospect of going to a concert alone. I texted my friend Suah and vented about how terrified I was and if I should just skip going altogether.

Something snapped in me when I read her texts, because she was absolutely right. Of course it would be awkward and painful but it would be worth it. It was a once in a lifetime moment, and I did like his music like crazy. If I did not go, I was shortchanging myself.

So I went, alone, ticket unsold unfortunately, and oddly it was one of the most liberating things I have ever done. I will be honest: I was half dissociating on my way there, and it helped that everyone was speaking French around me and I was walking around in a confused daze. I didn’t talk to anyone, foregoing looking at anything at the merch stand. I probably stayed in this strange daze all the way till the end of the night. Because it ended so late and I was in Paris—where nothing works when you need it to—my regular route home was not functional and I had to take a route I had never taken before, in an area I’d never been, at a time I was never out alone. I had to take a metro for what seemed like the whole line, before getting out and walking over to a tram station to catch a tram near my place. It was this moment when I climbed the stairs out of the metro station and into the dark night that I finally felt myself become conscious again. It was incredibly dark and quiet and cold. The streets were completely empty, except for couples or lone people trudging home, or a man walking his dog. I knew I was meant to feel terrified but in the moment I felt something akin to a punch to the gut, except in a positive way, if that was possible. It’s that feeling when you look around you and realise that you really are completely alone. The world is vast around you, and you are completely alone, and insignificant, and somehow that is beautiful.

I don’t really know how to explain this; I’m reading over what I wrote and I know that this should be incredibly scary. But in the moment I’d felt so at peace, like all the life I had lived in the world had come right to that moment (what a Kaytranada concert does to you). I was so delirious with the high of this moment that when a guy catcalled me as I was walking to the tram station, I barely flinched or got scared. In fact, I remember being almost giddy, exuberant because I understood what he leered at me in French, instead of being lost in translation. I think now I’ve been converted into a solo concert enjoyer.

When people ask me how I find Paris I always talk about how much I love being here, then I have to add, “Well maybe it’s because I’m living alone here, I appreciate it more. I feel more like myself.” I think this is a big reason. I have my own place, so I cook for myself and clean for myself and go grocery shopping for myself. I hate doing all of this, but being able to decide whether I eat or starve, whether I walk in the debris of my fallen hair or sweep it up, or whether I have an empty fridge or not gives me an incredible amount of freedom. Of course, I don’t actually live in filth—maybe my mother would disagree—and in fact, I feel like I’ve never eaten healthier in my life. In the beginning I really hated being alone: I didn’t leave my place for a week in fear of running into someone in the corridor and having to talk to them in French. I still really hate going grocery shopping alone, but I don’t need to pep talk myself before leaving the house anymore.

Around me my friends here are all used to this lifestyle of managing their lives and being alone. Most people have lived abroad or stayed independently or with their friends or with partners; no one stays in their family homes. They all shop for groceries regularly. They have bustling social lives, with an incredibly active lifestyle—whether gym or CrossFit or cycling—and party as hard as they study. They are chic and well-dressed. They speak multiple languages and moved around Paris effortlessly, unafraid of speaking bad French to waiters and service staff with intentions to practice the language more.

When I saw all of this happen around me I felt like life had shortchanged me. I think maybe everyone grows up with some form of complacency that the life they are living is the best kind. I think best kind is the wrong way of putting it; it’s more like I saw myself as the frog in the well who finally jumped out and saw the huge world stretching out before it and frogs leaping everywhere in that land. I don’t think this is a Paris thing, but maybe the freedoms afforded to the West where people are allowed to live freely, indulgently, shamelessly, fully (of course, if you have the financial means for it too).

I come from a household where my parents were very involved in our lives right from the beginning. I have a weird aversion to doing anything spontaneously, because when I was a kid my parents had a rule to give them two days notice before asking for permission for anything, and also to never plan anything on a weekend. I don’t ask for permission to do things anymore, but I am expected to report back everything I do—for safety reasons—and we have long discussions about what it means to be in a family unit and being together; where “individuality” and “being your own person” are never cards in the deck.

I’ve weirdly blocked out a lot of my teenage years because of how painful some of our arguments could get; arguments about selfhood and freedom and the typical stuff teenagers would want and parents wouldn’t. It is the sort of thing that hits me like whiplash when I see the life that my youngest brother lives and unwittingly find myself comparing him to me when I was his age. I don’t really want to get into the details of this, because at the end of the day I understand it is an immense privilege to have parents who are so deeply concerned with me and my life, and I know that for what it is worth, my parents do everything with purity and good intention. At the same time it doesn’t change this strange internal battle I’ve dealt with, and the liminal space between being dependent on your parents as a child and trying to grow into an adult. Growing up feeling so constrained sort of moulds you into imagining constraints that aren’t even there, like that elephant who still believes she can’t move anywhere because she used to be chained, despite not being chained anymore. (A lot of animal analogies today.)

I think it can become unfair to blame my parents, when it’s really society as a whole. In Indian households—at least for many of my cousins and also the generations before me—no one is really independent until you get married, and even then you are shackled to the duties you are expected to carry out for someone older or younger; sometimes I’d say people don’t even know they have these cold and biting shackles on their wrists, and seem to wear them in bizarre pride. In Singapore you’d think things would be more modern and First World, but instead we have our regimented education system, after which we encounter Adulthood—defined by good university courses and good corporate jobs with good salaries and a marriage and a house under your name.

It feels like a ridiculous blame game I’m playing—is it the overbearing way I’d been raised, or the overbearing culture I’m from, or the overbearing society I grew up in? I think when I started having these realisations and making comparisons to the people around me—all in my age range, yet far more self-assured and Adult-like—that I realised I was impressed by them, but also strangely immensely hurt and angry, as if someone had personally done this to me. Maybe it’s because we grow up thinking as Asians we are so smart and hardworking, but then here I realised everyone here was arguably more intellectual, passionate about what they do, with skillsets that had them existing completely in the real world whilst we kept practicing, existing in the simulation.

This led me to one of the biggest realisations I’ve made—besides the seemingly anthropological or sociological assessment of twenty-three year olds across different parts of the world—that I have free will. I mean, obviously I knew that before; I have all these understandings of the world around me rooted in spiritual beliefs where we control our lives and the world is what we make of it and everyone is a part of each other. But coming to Paris has made me comprehend it in a different way—I understand myself better now, I understand the world better now, and I also understand my power in it, moving forward. Being completely alone and independent all of a sudden forces you to question how you have lived your life, and how you’d want to continue. Everyday I fight an internal battle where someone—myself—tells me that I can’t do something. I look to people around me for answers, to help me make decisions I run away from making, to give me some form of approval. I don’t want to continue existing in this vacuum, alternating between blaming myself and blaming someone else. I realised I really want to just be.

Of course, besides all this, I really do love Paris. Of course, I love the typical things about it—the art, the Eiffel tower, the beautiful buildings, the thrift and vintage stores packed to the ceilings in fashionable fabrics you could never find in Singapore, the view of boats passing as you sit by the Seine or by Canal Saint-Martin, sitting at a cafe in le Marais and watching the most fashionable people walk past you while your croissant drops in flakes on your clothes. And also, I love Paris in all its grit and inefficiency and filth. I adore when people are openly intense and randomly break out in fight. I like walking past the walls of graffiti and reading the phrases and realising I agree with all of them (everyone is such a socialist here). I like seeing people be unabashedly themselves, instead of hiding behind façades of decency. Everyone here has what I call a DGAF mentality. I wouldn’t go so far as to piss in public or condone it in any way, but I think my solitary grocery shopping and complete ownership of my resting bitch face feels like a step towards achieving a DGAF mentality.

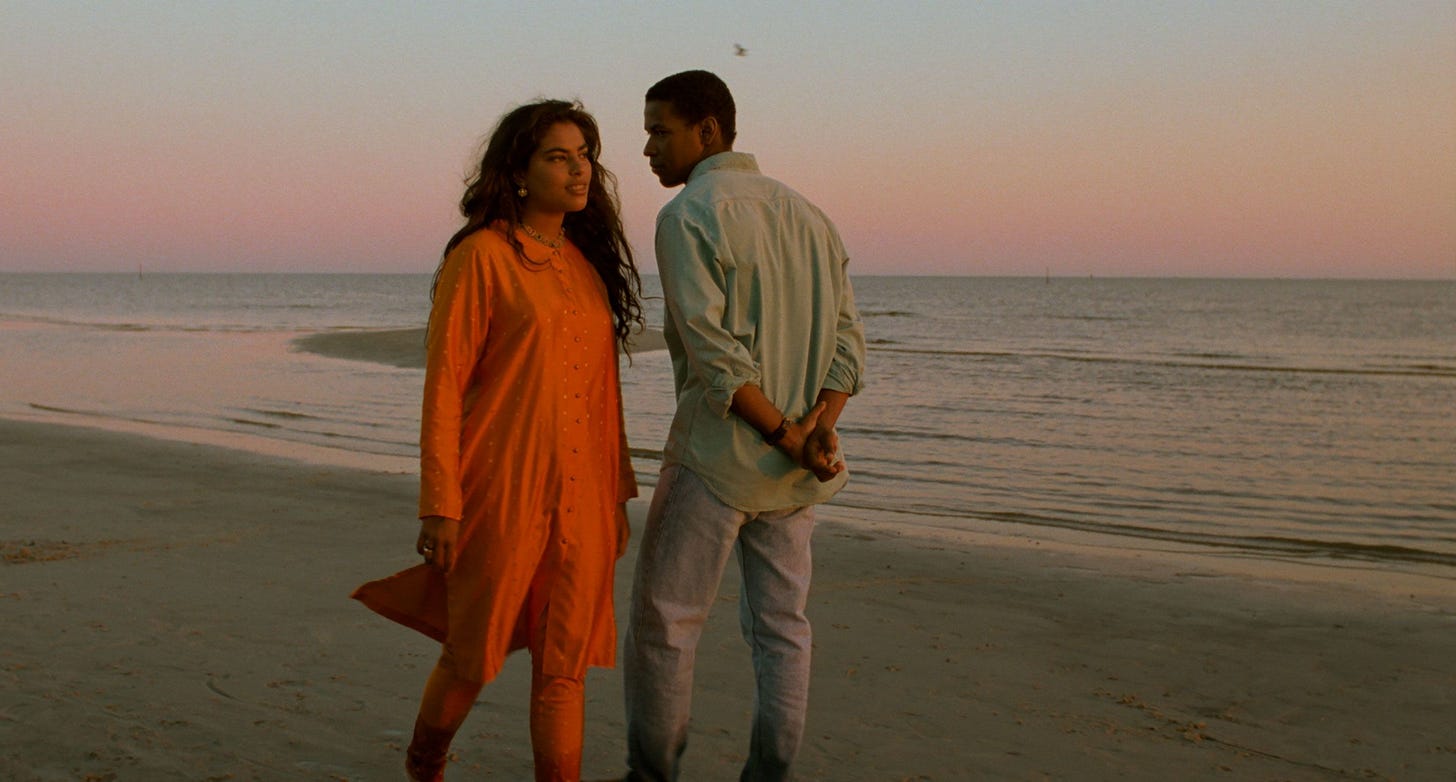

A few days ago I finally watched Mississippi Masala (1991). It’s been on my Letterboxd watchlist forever, mainly because I thought the two leads—Mina (Sarita Choudhury) and Demetrius (Denzel Washington)—were incredibly attractive and I liked some of Mira Nair’s works. I watched the characters fall in love, and fell in love with them myself (decided that my dream man would be none other than Denzel Washington).

The film surrounds an Indian-Ugandan family who is forced to flee Uganda during the regime of Idi Amin, and end up living in Mississippi, America. Amin was a brutal dictator (backed by Isr*el for a long time, interestingly) who decided that Asians, most of whom were Indian-Ugandans, were not real Ugandans and therefore should leave the country, which belonged to “Black Africans”. These Indian-Ugandans were descended from the Indian people brought to Uganda by the British to build the Ugandan Railway generations before, and ended up left in the lurch. In the film Mina’s father Jai (Roshan Seth) is distraught about leaving his home, and keeps finding ways to contest for Ugandan citizenship despite being miles away from Uganda. Actually, all of this is just the background of the film; it is really about his daughter Mina who falls for Demetrius, a young local African American boy, and the fallout they are forced to deal with.

Most of the time I struggle to connect with a lot of mainstream Indian media, and also diasporic media. Bollywood today sits on a spectrum of war propaganda, and almost ridiculously mindless portrayals of the modern sexually liberated woman; and all these projects are filled with nepo babies—an attempt to please the fascist government and its rabid bigoted fans, the neoliberal youth, and the Bollywood stars who worry about their children being unemployed. Diasporic poetry can be incredibly cringe and painful to read (I will never want to read about a mango again). Television shows like Never Have I Ever and Bridgerton’s Season 2 definitely try to present an experience that is authentic to the South Asian disapora, but besides the heartwarming inclusivity I haven’t found or watched a lot that actually touches me and makes me feel seen.

I would not say Mira Nair’s work represents it completely; my parents are not definitely the type to sit around and talk about needing their daughters to get married, or worry about shame falling upon the family. Maybe this is because she is Indian-American, and therefore her interpretations and portrayals of the diaspora might not completely reflect South Asians everywhere; the diaspora itself is so diverse and broad, that there is no way to singularly define it. But somehow, this film manages to capture this liminal space between your country of origin, and the country you live in or say you belong to now. I’m not even particularly sure how to explain this myself. Maybe it was seeing Sharmila Tagore on the screen (the gasp at the familiar face) or finding the characters reminiscing to the same old Hindi songs that your grandfather plays when he is in the mood to drink a glass of scotch. I found this feeling of being seen so strange; I wouldn’t even say I ever yearn for or am homesick for India either. I don’t find myself being extremely eager to go there in the near future, unless of course I am obligated to by my parents. In fact sometimes I struggle to identity as Indian or Singaporean because I don’t feel authentic in identifying as such. I think seeing familiarity within this film reminded me that, no matter what, I will always have those roots even if I feel foreign to it.

Actually, one thing people back home have asked me the most is whether I feel homesick. Sometimes I felt guilty for my honest no. What was there to feel homesick about? I think I can be like an infant because I have some form of object impermanence. The only real times I missed Singapore acutely were the 2-3 week-long holidays my family used to take to India, where I longed for real showers and internet access and normal skin instead of the water in a bucket that we were presented with and the cracked and bleeding skin I would be left with, no thanks to the dry climate. Otherwise when I’m abroad I’m usually completely submerged in my physical surrounding, with no room left for homesickness.

I miss Singapore the most when I see the meagre and thin rain in Paris. Rain here falls almost pathetically; you don’t feel the water, instead you feel the wind blowing at you and shredding you to quivering pieces. I think of the raging thunderstorms, the trees and leaves battling viciously with the wind, the lightning that strikes like a slap in the sky, and the water falling like blades onto the ground. And us, in our beds, rubbing our feet beneath the sheets. I also miss Singapore when I’m hungry—I miss the Thai basil chicken, the hawker centre food, the Wingstop and Potato Corner, the prata, the food in Little India (I would say Lingham’s Extra Hot sauce too, but I brought that along with me). Actually I miss the long drives at night on Singaporean highways with my family, existing when the city is asleep, cutting through the air with intense speed; the walks with my sister, sitting in the dark while the humidity sits on our skin.

What was it I longed for? For the past week, even before watching Mississippi Masala, I found myself thinking of and playing old Hindi songs, and when I listened to them I was suddenly brought back to days I hadn’t remembered in forever. In themselves any form of old music makes you feel nostalgic for an era you don’t belong to. But also being so far away and all alone imbues another hue into this melancholic feeling. Strangely I understood my father and even my grandfather more than ever; the way they loved to play old Hindi songs and never tired of it, like a gateway into another world. Now I was nostalgic not just for my childhood, but their memories too, when they first listened to these songs, but also the era in which this music was created, one I can only experience through this music and the films they accompany. Actually, music feels like an easy way to sink into the past; when I miss my mum or dad I look up songs that remind me of them, and it takes me back to the moments they’d play it in the car or on Youtube. In those moments my siblings and I would demand that they change it to something we liked more, but now I voluntarily search those up.

I don’t want to return to the past, but maybe that’s something I am homesick for, the way I felt back then. Or maybe it is just normal to always look back in nostalgia, the human need to mourn what won’t come back, to manipulate temporalities and recreate the past in the present.

I took a long break from writing. The truth is that I felt like I had lost something in me for a while. There is always a voice in my head that starts to speak in long sentences that inspire me to jot down somewhere, but for numerous months that voice was completely silent. I don’t really know what it is; maybe I just stopped thinking. I also feel like I didn’t believe in myself to add any words of value to anything, when everything happening in the world feels so much more important than anything I have to say. But also I was trying to exist more openly and presently in the world, without being in an active pursuit of finding something to write about and foregoing being mindful. (Did it work? I’m not sure.) Actually, this is kind of an extension of what I was feeling when I wrote this. I’m still in that mental phase, and trying to shed it and become more.

Either way, I’m trying to make a more marked return to my writing practice. Hopefully I write more to follow this up with.

Beautiful, Paris is lucky to have you

Denzel breaking your writer's block